In the case of an extension or conversion to a historic farmstead, non-designated building in a conservation area, or listed building, the applicant must demonstrate that the proposal respects the character and appearance of the building and does not harm its significance or setting. Impact on surrounding heritage assets will also need to be considered (see ‘Heritage Assets’).

In cases where the structural condition of a building is in question, a full structural survey by a qualified architect or structural engineer will be required prior to application.

The original function of farm, industrial and other traditional buildings must be legible when converted.

When converting a traditional building, the fundamental plan and massing must be maintained, and insertion of new openings, or blocking of existing features, must be kept to a minimum. Where changes are proposed, these must be accompanied by a clear statement of need and assessment of impact on significance.

Checklist for conversions of agricultural, industrial and other traditional buildings for residential use:

The applicant must demonstrate and clearly articulate how the proposed development respects or enhances local character and distinctiveness. This must be informed by an understanding of the site context, including any historic character assessment required to support the application.

On a local level, understanding the physical, cultural and spiritual factors that shape place identity is a critical first step in the design of conversions that preserve and enhance local character and make a positive contribution to placemaking.

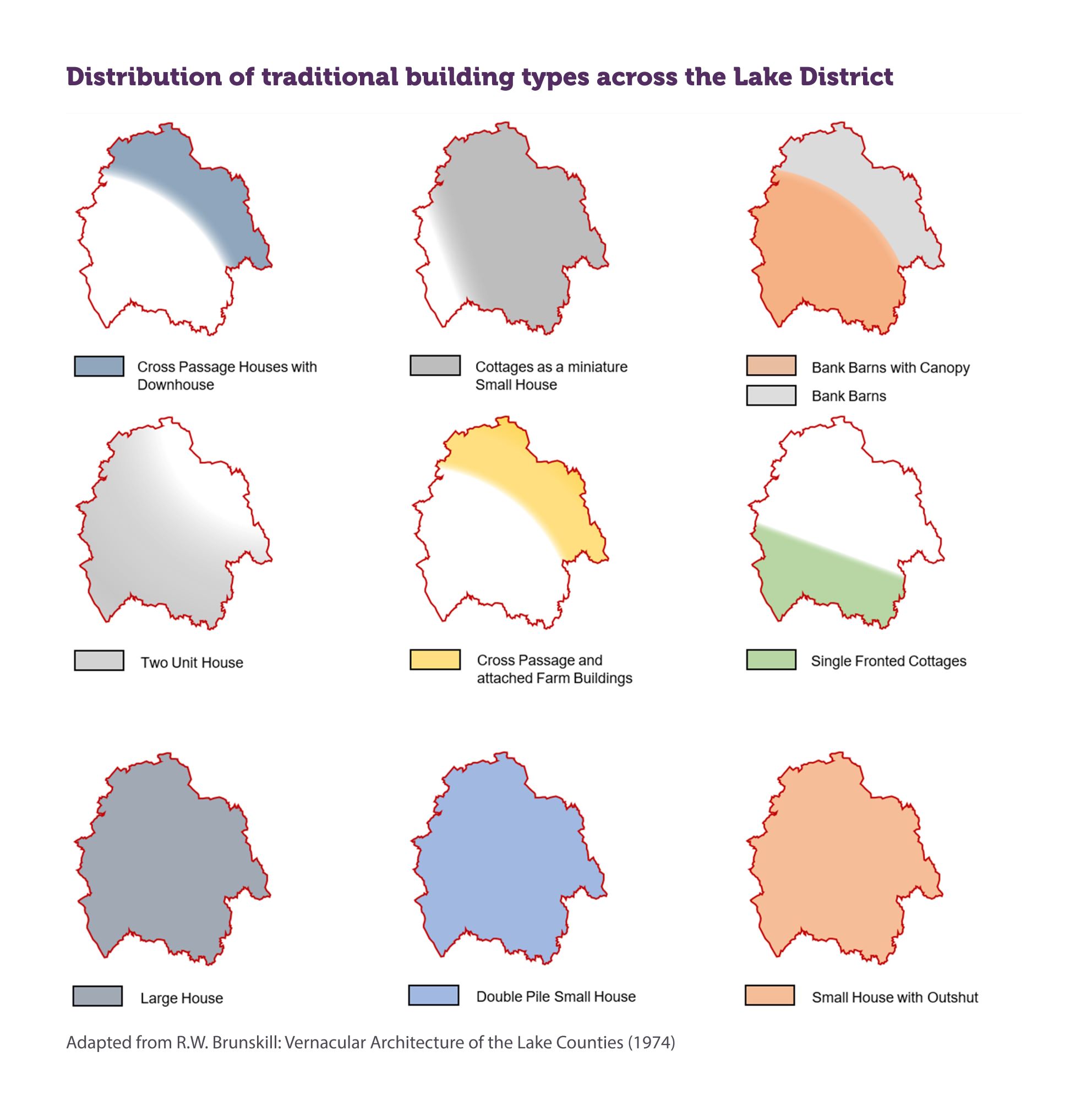

The type, form and composition of conversions must be rooted in local character. The design of conversions must reflect the local vernacular architecture and traditions. Vernacular design is architecture based on local materials and traditions (where buildings were designed to meet functional needs). Vernacular architecture varies across the Lake District in response to changes in the underlying geology, that influences not only the choice of local building material, but also built forms and methods of construction.

Information on common vernacular forms, and their distribution across the Lake District, can be found in the Supporting Information. Each settlement has a distinct architectural tradition depending on several factors, but common characteristics are:

Although these features are common there are many variations according to location and designs need to respond appropriately to the specific traditions of the area. This is not intended to stifle contemporary design or encourage pastiche, but simply show how a design has been inspired by local character.

Click to zoom in.

The type, form and composition of new buildings must be rooted in local character. Where development sits within the historic core of a settlement, design must reflect the local vernacular tradition (where buildings were designed to meet functional needs). This varies across the National Park in response to changes in the underlying geology, that influences not only the choice of local building material, but built forms and methods of construction.

Information on common vernacular forms, and their distribution across the National Park, can be found in the Supporting Information. This is not intended to stifle contemporary design or encourage pastiche, but simply show how a design has been inspired by local character.

In areas where there is a wider variety of architectural styles, particularly those areas of 19th and early 20th century expansion around the edges of towns, design cues should still be taken from the prevailing architectural forms of the area, although there is potentially far more flexibility in design. However, detailing should be consistent with architectural style, and mixing features within a building should be avoided. In all cases, design must be informed by analysis of context and local character.

Windows and doors often make the most difference to the finished appearance of conversion and are manufactured in a range of materials. The most common are wood, uPVC and powder coated aluminum.

Wooden window frames and doors will normally represent the most appropriate and sustainable option. They can be designed in ways to respect the character of any building and can be painted and repainted in any colour without replacement. If looked after and properly maintained, they will last for many years. They can be constructed to be as secure and weather-proof as uPVC windows.

UPVC and composite windows and doors come in a limited range of colours and designs. Storm casement uPVC windows (where the opening pane overlaps the frame) are the cheapest and most common window frame in use but they result in the least satisfactory appearance on houses in the Lake District. Because they are not symmetrical, they cannot replicate the appearance of a traditional casement window or a later sliding sash window which are normally symmetrical in appearance. Combined with their thick frames they are rarely an appropriate choice for a building of traditional character or one which contributes to the wider character of the area.

The use of standard uPVC storm casement windows is only likely to be acceptable in a limited range of circumstances where their use has no overall impact on the character of the building or the wider area.

Significant advancements have been made in UPVC windows. Both convincing high quality sliding sash windows and flush fitting casement uPVC windows (where the opening part of the window sits flush within the frame) which replicate traditional window types are now available. These will be considered on a case-by-case basis but will nearly always represent a more appropriate option than a uPVC storm casement window.

Powder coated aluminium frames come in a large range of colours. They are also thinner than uPVC windows so have a wider range of uses. They are often used successfully on contemporary buildings.

In some conversions, factory finished Accoya windows will not be appropriate.

The colour of windows and doors is an important part of the appearance of a building.

Darker colours are more appropriate for barn conversions rather than hew housing schemes because it is often necessary to reduce the impact of new windows and doors as far as possible, to avoid compromising the agricultural character of the building.

Anthracite Grey (dark grey) is currently a very popular choice. This colour tends to work well on contemporary rendered buildings, providing a contrasting colour with lighter rendered walls. However, it provides no contrast with buildings which have darker walls or stone walls.

Whites and off-whites which provide a strong contrast with local stone walls are normally the most appropriate choice but a range of colours including light greys, greens and blues will complement the subtle colours found in local slate and stone.

Where planning permission is not required for the replacement of windows and doors, we strongly advise that existing traditional or original windows are retained and refurbished where possible but that any replacement considers the appropriateness of the design, materials and colour to the character of the building and the area and also takes into account longevity, value for money and carbon footprint.

The distribution, size and design of window openings, glazed doorways or other glazed apertures in conversions must:

The darkness of the night skies is a key characteristic of the Lake District that reflects its rural character. The skies achieving complete darkness is also of ecological importance. The unwanted impacts of light spill and highly reflective glazing can be avoided via the following measures:

The colour and textures of materials in conversions must harmonise with local character and landscape, although this does not prevent the use of both to add focus and interest to the streetscape where justified.

Stone used for the walls of buildings must match the type, appearance and method of laying that is most prevalent in the area.

Only where it is not possible to obtain stone which is typical of the area will alternatives be considered.

Roofing materials must be Westmorland green slate or blue grey slate laid in a traditional pattern of diminishing courses (where larger slates at the eaves gradually recede to the smallest slates at the ridge) and random widths.

Alternative roof coverings to local slate will only be considered in the following circumstances:

National policy and the Local Plan support development that reinforces local distinctiveness, character and sense of place.

One of the most important ways of establishing a sense of place in the built environment is through the use of materials, most importantly through roof and wall materials. These should be complimented with an approach to windows, doors, landscaping and boundaries which reflect the quality of the landscape and the importance of the built environment.

Unlike other areas of the country where building materials are often imported or manufactured, the appearance of buildings in the Lake District is a direct product of the geology beneath them.

Whether it’s distinctively pink Eskdale granite or it’s the greens and greys of Honister stone in the centre of Keswick, when planning a design for a conversion in the Lake District, looking at the roofs and walls of your neighbours is often all that is necessary to help inform what the most appropriate approach should be.

Most locally distinctive of all are the local slate roofs of the Lake District that can be seen covering the majority of buildings in the area and which make a significant contribution to sense of place, particularly when seen from above. Local slate has a thick gauge, rough hewn surface and distinctive pattern which all contribute to an appearance that is as locally distinctive when first laid as it is decades later.

The use of Westmorland green slate or blue grey slate will be informed by the immediate context of the site. Often, either option will be acceptable.

Imported slate is not an acceptable alternative to local slate. This is because it is likely to retain a smooth and uniform colour and texture which means it does not weather in the same way as local slates. As they are normally made to standard sizes and to a thinner gauge, they cannot replicate the variety found in a local slate roof and cannot replicate its appearance.

Where planning permission is not required for replacement or repair of an existing roof, we strongly discourage the use of imported slate because the incremental effect of changes which do not require planning permission is the erosion of local distinctiveness, character and sense of place.

If there are valid reasons to consider roof coverings other than local slate, alternative locally produced roofing materials are likely to be more appropriate than imported slate, when considered in terms of its appearance, longevity, value for money and carbon footprint.

The walls of a building can often be as important to local distinctiveness, character and sense of place as its roof, especially within a dense town context or a tightly knit farm group when seen from road level. Wall finishes are functional, decorative and often both.

Local walling materials vary more obviously across the Lake District than roofing slate. Stone is less easy to transport and therefore historically, the easiest stone to build a house or barn from was the closest available. Walls were often built upon boulders or bedrock, with stone quarried from the nearest rock face or gathered from the land or nearby streams. Most buildings constructed in this way using ‘found’ rubble stone would historically have been externally finished with a lime render and limewashed.

Because it is a by-product of slate manufacture, slate stone remains the most common walling material for buildings in the Lake District, with limestone, granite and red sandstone used in outlying areas.

Roughcast render or ‘wet-dash’, or modern products which replicate its appearance, is the other most common walling finish. Roughcast render is used throughout the Lake District and its use as a wall finish is likely to be appropriate on a range of buildings, particularly where it is not possible to obtain stone to match nearby buildings.

Agricultural buildings, with the exception of farmhouses, were generally not traditionally rendered in the Lake District. This made a clear distinction between domestic and functional space. Unless evidence can be demonstrated on the building itself or through research, former agricultural buildings must not be rendered.

It will be necessary to demonstrate that the use of materials other than local slate, stone and roughcast render is appropriate.

Metal wall cladding (including zinc, copper, lead, stainless steel and aluminium) and timber wall cladding or composite cladding products which mimic the appearance of timber are only likely to be acceptable where used sparingly as part of a cohesive design solution and where the context of the site and character of the landscape means that its use would not compromise sense of place.

Large areas of glazing do not reinforce local distinctiveness or sense of place. Large areas of glazing can also result in light pollution which both national policy and the Local Plan seek to avoid. In sensitive landscape locations the extensive use of glazing is unlikely to be acceptable.

Hard and soft landscaping and boundary features including gates fences and walls must respect landscape character and sense of place and must be included in all proposals where wider landscaping, new or altered accesses or new or altered boundaries are proposed.

With a large or prominent development, including conversions to buildings in a sensitive area, the way the development interacts with the landscape beyond its boundaries can be equally as important as the appearance of the building itself. The entrance and boundary walls is the place where private space meets public and where the influence of your development on the landscape and can be felt most.

Stone boundary walls will normally be the most appropriate option. Stone used should reflect existing stone walls in the area in terms of type of stone and method of laying. Dressed stone is not normally used for boundary walls. Other boundary types such as native hedge planting will be considered where this is consistent with the other boundaries in the area.

Large entrances will rarely be appropriate in the context of small-scale vernacular buildings and in sensitive rural landscape locations.

Hard landscaping should be kept to a minimum and must take cues from the surrounding area, subject to associated constraints such as drainage and durability. The choice of surface must harmonise with local character particularly in terms of colour.