Supplying the mines and the miners

Historic documents shed a little light onto how the mine was tied into the surrounding community. During the 1860s and 70s the mine company bought thousands of candles from suppliers in Kendal, Ulverston and Preston. Hundreds of hundredweights of coals were shipped up to the ‘copper station’ from Wigan, to heat the pitmen’s houses and power the Thriddle machine. Enormous quantities of gunpowder in cans and casks were exploded, obtained from Elterwater Gunpowder Company and other smaller suppliers. From 1877, receipts for dynamite, caps and cords appear in similarly large quantities.

The mines company seems to have used the same suppliers for many things. For example E Salmon and Co supplied the stamp heads and stamp plates for the stamp mill, lever sockets, pull plates, rods, wagon wheels, ratchet wheels, small pulley wheels, big pulleys for shafts, and big half-rings for the wheel. This supplier was involved in a major court case over invoices which the mine angrily disputed.

For general work up at the mines, there are records of purchases of shovels, spades, rope, barrels of tar, pitch, grease, whips, pick and hammer shafts, oil, horse gear, larch poles and a number of trees, as well as dozens and dozens of brooms. Accounts relating to horses and their equipment show that horse shoe nails were bought by the thousand, while oats, corn, beans and bran were delivered by the sackload.

Transporting the ores for processing beyond Coniston

In the 17th century the processed and prepared ore was transported by packhorse. At Keswick there were smelters, although ore could only be taken there in the summer, when the routes were passable. In the spring of 1602 as many as 500 local people were employed to move ore to Keswick, probably to make up for lost time over the winter.

In the 18th century, packhorses travelled instead to Coniston Water. Boats took it from the company landing place at Coniston Hall Farm onto Nibthwaite at the south end of Coniston Water, then to Penny Bridge or Greenodd and finally onto smelters in Liverpool. In 1843 the mine company had built a warehouse at Nibthwaite Quay, where ore awaited forward shipping. At first it went to St Helens. After a dispute it headed instead to the famous Hafod Morfa copper works, Swansea.

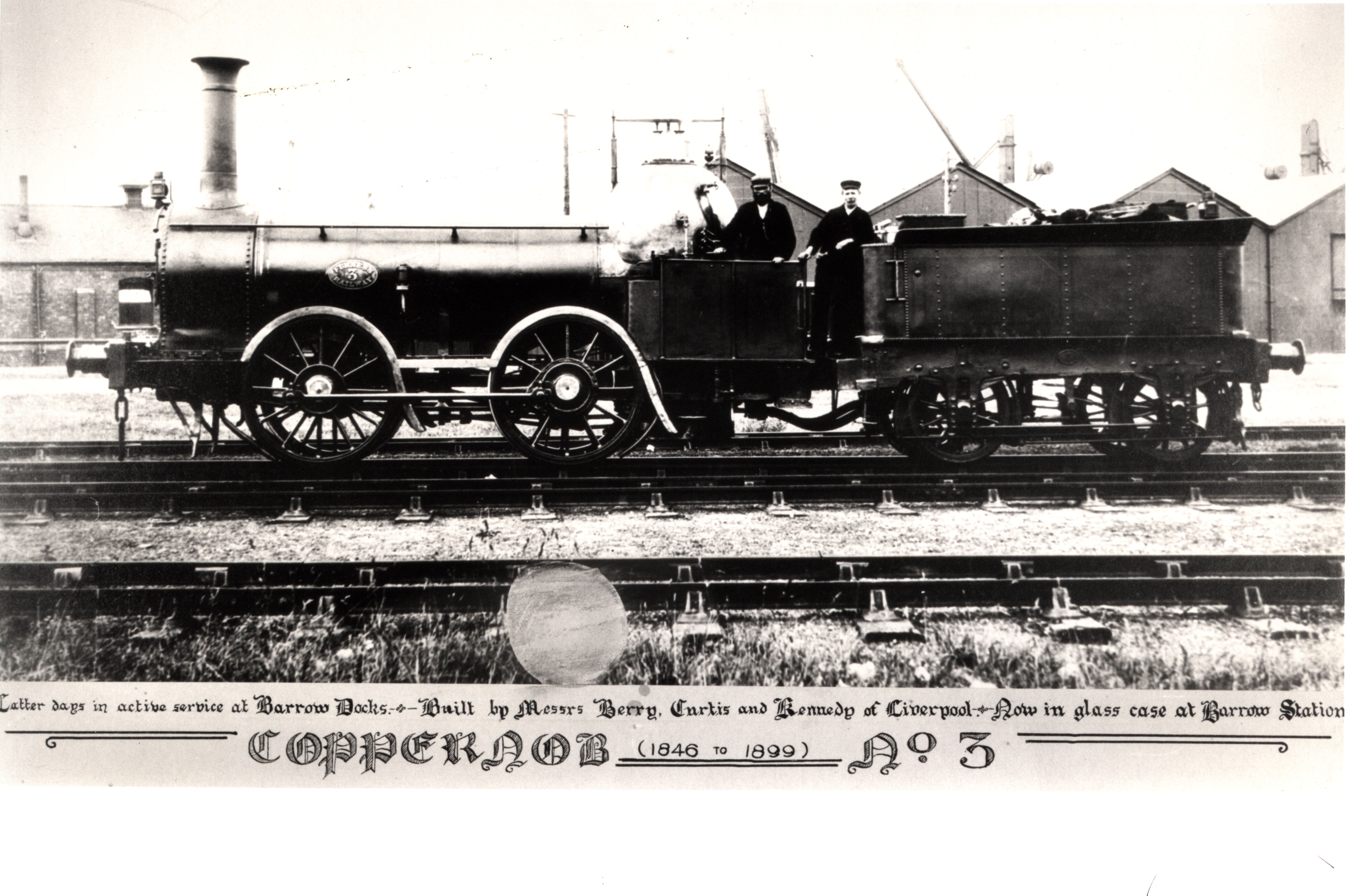

In 1859 the Furness Railway was linked into Coniston. Miner’s Bridge was built especially to cart the ore from Bonsor Mills to a depot at the base of the hill. From here the railway company hauled it to the station.

How the Elizabethan mines were operated and supported

Until the reign of Elizabeth I, England imported copper. Needing brass cannon to defend itself, reliance on copper imports was a strategic weakness. English mining was still primitive and could not cope with copper. German-speaking miners, however, particularly from Augsburg in modern Bavaria, were the world’s experts. The Society of Mines Royal was formally established on 28th May 1568 with a monopoly on minerals underground. Along with the Company of Mineral and Battery Works, established on the same date, it was the first joint-stock industrial enterprise in England and the forerunner of the modern company. This company was made up of German and English shareholders and provided a vehicle for raising large amounts of capital by selling shares to investors.

Early problems were that the English shareholders were suspicious of their German partners, and that it was difficult to collect investments from unwilling shareholders. In 1579/80 Daniel Hochstetter Senior took a 5-year lease on the Lake District mines. Now the shareholders would receive rents, and the liability for expenses and losses passed to the lessees. This system was often referred to as ‘farming’ since it mirrored the relationship between landowners and their tenant farmers. On Daniel Hochstetter Senior’s death in 1581, his interest in the lease passed to his sons, Daniel Junior and Emmanuel. By 1599 both sons were managing a copper mine at Coniston and in 1604 James I confirmed the charter of the Society of Mines Royal, including the names of both Emmanuel and Daniel Hochstetter Junior. James I had less of a requirement for brass cannons, and production costs had increased as mines went deeper. In May 1620 Hochstetter wrote “The old Myn at Coniston is now quite given over not a thing theyr to be had”. The Lake District mines, still managed by the Hochstetter family, closed around 1630, and the association of the Society of Mines Royal with this part of England was finished. Until 1688 nothing was mined in Coniston, at least not officially.

Financing the Coniston mines from 1650 to 1810

In 1655, Sir Daniel Fleming inherited his estate, including Coniston Manor. The Crown still owned the mineral rights and so there was no incentive to mine. In 1688, however, the Royal Mines Act removed the Crown monopoly. The removal of the Crown monopoly meant that landowners, including Sir Daniel Fleming at Coniston and the Pennington family, whose Muncaster estate included nearby Tilberthwaite, could operate mines for their own profit. They could also lease mining rights in return for a share of the profits and over the next 60 or 70 years both estates made a series of leases. None were successful and none were renewed.

Between 1756 and 1762 the merchants Charles Roe, of Macclesfield, and Anthony Tissington, of Derbyshire, took out leases with the neighbouring Fleming and Muncaster estates respectively. Between 1758 and 1763 Roe’s associates took over Tissington’s leases and controlled most of the Coniston copper-mining rights. In 1774 the Macclesfield Copper Company was formed and in 1778 Charles Roe renewed his lease for a further 26 years. Gunpowder meant that his progress was fast, and veins could be followed well below the older German workings. Roe died in 1781, his eldest son William took over and the firm continued to work at Coniston until 1795 when they abandoned it as unproductive. Between 1803 and 1824 William Evetts of Sheffield leased the mine, although apart from a short-lived revival during 1809 not much was done.

An account of the heyday and decline of the Coniston mines

In 1824 John Taylor arrived with his manager John Barratt. He leased mines and veins in the manor of Coniston from Lady le Fleming. In 1826 Taylor and Michael Knott entered into a leased from Lord Muncaster for all minerals in Little Langdale and Tilberthwaite. The Coniston lease was renewed in 1834 as the copper mines became busy again. In 1841 John Barratt bought out John Taylor and his partners, and in 1853 he also took a lease in the Muncaster estate at Tilberthwaite. In 1857 Barratt, together with Lady le Fleming, subscribed to shares for the Coniston Railway to pass near the copper mines. In 1864 Barratt renewed his Tilberthwaite lease for 21 years, but then died in 1866. By then the output had begun to decline due to the costs of maintenance.

In 1875 the mine’s assets were sold to Thomas Wynne, and a 21-year lease was signed in 1878 for the Tilberthwaite mines. By 1884 the mines were partially closed as copper prices dropped due to cheap imported ore. The Coniston Mining Syndicate was incorporated as a limited company in 1892, with a new 21-year lease from the Fleming estate. By 1896, however, Penny Rigg at Tilberthwaite was producing slate, and there were no longer any workers active at the Coniston mine. In 1908 Coniston Mining Syndicate was wound up and Fleming obtained a judgement for possession.

In the 1910s the Coniston Electrolytic Copper Company, under Count Henri de Varinay, started processing the spoil at Coniston, Tilberthwaite and Greenburn. They used a new process for recovering copper from ore previously discarded as waste. By 1914 the project was abandoned.Remaining waterwheels were removed as scrap in the 1930s. The last of these to go was the wheel from Bonsor Upper Mill in 1939. Some prospecting took place in the early 1950s but the mines were left to rot until recently.