Overview (click on the links to visit the page sections)

The Lake District is mountainous with valleys modelled by glaciers in the Ice Age and then shaped by pastoral farming characterised by fields enclosed by walls and commons. The combined works of nature and human activity has produced a cultural landscape in which mountains are mirrored in the lakes.

In the 18th-19th centuries, this landscape attracted wealthy industrialists and entrepreneurs keen to develop villas, parks and gardens exploiting the beauty. Today, we see these changes as adding to the Lake District’s iconic distinctiveness along with its agro-pastoralism, settlement and local industrial heritage.

A key feature of our landscape is the entwined relationship between natural environment and farming. Our farming systems have adapted to operate in harsh upland environments, such as specifically adapted livestock breeds like the Herdwick. In turn, farming generations have created the landscape character through their buildings, boundaries and farming activities. Looking forwards, farming will be necessary as part of nature recovery, climate action and the visitor economy.

This page, explores the cultural character of farming practices by recognising a range of features and activities important to the uniqueness of the Lake District. There are diversification opportunities to enhance your business in line with the new Government agenda of public goods. These are goods and services that no one can be stopped using and where one person’s use does not affect another’s, like public access. Lakeland farms also help to underpin the economic and social resilience of our rural communities.

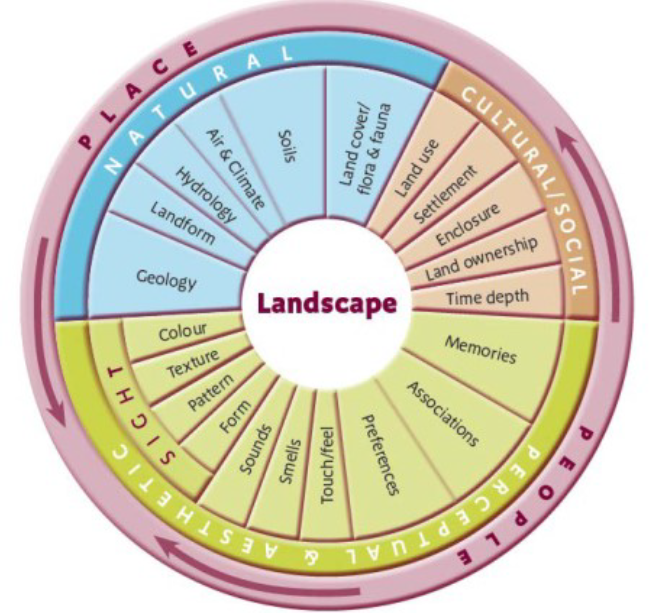

Cultural landscapes are more than just buildings and boundaries. They are made from all the activities we carry out, how we work together and how we adapt the land to make farming work. This diagram shows how many aspects of the places in which we live, the people we are and the things we do come together to create a cultural landscape. Landscapes are, consequently, a product of many tangible structures and intangible processes. They also constantly change, which needs consideration. The landscape of yesterday is not necessarily the landscape of tomorrow.

Diagram: Aspects of the places we live that create a cultural landscape

The Lake District has so many special qualities derived from the cultural landscape that we are recognised internationally as a World Heritage Site (as well as a National Park.). Three key themes have allowed this inscription to occur, known as our Outstanding Universal Value (OUV):

Here in the Lake District, our farming system has evolved within the limits of our harsh environment for thousands of years. Some of our most iconic tangible cultural structures are those which develop around stone farmhouses designed to aid in everyday farming tasks. Others are created by intangible farming practices, particularly those related to hefting, gathering and commoning, livestock management and community activities, like shepherds meets.

There are a huge range of vernacular Lake District buildings, all of which historically have performed crucial functions on farms. As farming has changed, the original use has become redundant and buildings can fall into disrepair. Repurposing buildings is not uncommon within farm businesses. Barns, in particular, can be sensitively adapted and reused for diversification opportunities such as: bunkhouses, small business venues or low impact visitor facilities. In doing so we can retain the external cultural fabric of our landscape, improve the farm economy and offer sanctuary for biodiversity such as bats, nesting birds and the more unusual plant groups, like lichens or ferns.

Image: Field Barn in Martindale

Field barns were a response to the problems of overwintering stock in the harsh Lake District environment. They were also an important component of the hay making system, but as hay fell out of use, stock overwintering drifted back to the main farmstead. With their original use gone, some are close enough to the road to be converted to houses or businesses; whereas those further way make ideal homes for roosting birds and bats.

Hog houses (sheep houses) were used historically to shelter sheep in winter. Dotted across the landscape many fell into disuse as stock were brought back to the inbye or overwintered elsewhere. Most are now used as outlying stores for fencing materials and so on. Maintaining their structural integrity is key to retaining the way our cultural landscape looks. Additionally, like barns, they provide ideal locations for bird and bat boxes.

Image: Hennery-Piggery at Troutbeck, South Lakes

Restoring and repairing structures such as this Dipping Tub (before and after) at Croasdale Farm, Ennerdale celebrates our cultural heritage. It helps keep traditional skills alive, which can be used for other projects, or for repurposing or reuse. Restoration and repair also helps tell the story of our farming landscape for visitors and local people.

Images: dipping tub at Croasdale Farm in Ennerdale before and after restoration

This peat hut or ‘peat scale’ pictured below, in Eskdale, was used to store dried peat ready for the farm fire. The open doorway shown allowed cut peat turves to be thrown in. Once dried, they were taken from a lower door on the other side.

Peat cutting was strictly controlled by the medieval manor courts and commoners were restricted to certain areas each year. Peat cutting continued in Eskdale until the 1950s. Now we value peat as a carbon store to help with climate action and encourage it’s restoration.

Image: a peat hut in Eskdale

From the intricate complex pattern of field walls in Wasdale, which could date from the Norse period (10th century), to regimented straight boundaries created by parliamentary enclosure from the 18th century, all of our drystone walls are important.

Image: stone walls in the Lake District National Park

Hedgelaying for Cumbrians means either Westmorland or Cumberland style, depending on your location. Good quality hedges need laying every 7 to 10 years, with intermittent standard trees and gaps filled with new whips.

The development of field boundaries and field systems in the Lake District probably started in the Bronze Age (2500BCE), where archaeological surveys on the south west fells has demonstrated the heaping of stone into linear boundaries. Between the 8th and 10th Centuries, our farming set the framework for much of the patchwork of fields and boundaries we see today. Place names, dialect words, trackways, farmstead locations, fields and enclosures, underpinned by our open fell commonland system are key elements from this time.

All these survive specifically because our pastoral farming practices have not changed much. Walls and hedges are therefore particularly important elements, not only historically, but because they now act as wildlife corridors between larger areas of habitat allowing animals to migrate, colonise and recolonise, increasing our biodiversity. From the intricate and complex pattern of field walls in Wasdale, which could date from the Norse period (10th century), to the regimented straight boundaries created by parliamentary enclosure from the 18th century, all of our drystone walls are important.

Hedgelaying for Cumbrians means either Westmorland or Cumberland style, depending on your location.

Image: Hedgelaying © Rusland Horizons Trust

Good quality hedges need laying every 7 to 10 years, with intermittent standard trees and gaps filled with new whips. The development of field boundaries and field systems in the Lake District probably started in the Bronze Age (2500BCE), where archaeological surveys on the south west fells has demonstrated the heaping of stone into linear boundaries. Between the 8th and 10th Centuries, our farming set the framework for much of the patchwork of fields and boundaries we see today. Place names, dialect words, trackways, farmstead locations, fields and enclosures, underpinned by our open fell commonland system are key elements from this time.

All these survive specifically because our pastoral farming practices have not changed much. Walls and hedges are therefore particularly important elements, not only historically, but because they now act as wildlife corridors between larger areas of habitat allowing animals to migrate, colonise and recolonise, increasing our biodiversity. In the past, conservation concentrated on protecting wildlife by creating nature reserves. Nature doesn’t recognise fences, species need to move around and migrate, depending on seasonal and climatic changes. Most species need areas of ‘prime’ habitat, interconnected through a patchwork of less suitable habitat through which they can move to get food, shelter and mates. Well maintained hedges and walls are ideal for this. Hedgelaying for Cumbrians means either Westmorland or Cumberland style, depending on your location. Good quality hedges need laying every 7 to 10 years, with intermittent standard trees and gaps filled with new whips.

Shard fencing is perhaps one of the most unusual boundaries we find in the Lake District. Made from upright slabs of blue slate, this example near Esthwaite Water, provides an effective stockproof fence. At the same time it supports a range of lower plants such as lichens and mosses.

Image: Shard fencing near Esthwaite Water

Lichens can be used as a method to date the structure they are growing on. With a growth rate of 0.3mm per year, a 8cm diameter lichen could be 267 years old!

This Sheepwash on Stevenson Ground was a typical sight across the Lake District fells. Farmers would wash their sheep before shearing as merchants would pay more for clean wool. These practices didn't use chemicals or soap, so whilst good for the environment, it is hard to judge how effective they were for animal welfare by today’s standards.

Images: Sheepwash on Stevenson Ground

Field systems in the Lake District are a complex pattern of different ages. Often rigg and furrow lie underneath a network of later rectangular fields divided by drystone walls, with the latter dating from the 18th and 19th Centuries.

Running out from settlements or farms are the outgangs; wall-lined tracks where sheep or cattle were driven up to or down from the fell.

Image: example of an outgang

All these field system features are in our ‘Top 20’ of what we feel are crucial to our Lake District landscape. They underpin much of the special qualities and OUV of our agro-pastoral farming system. If you have any of these on your farm please do get in touch as we would like to know more (archaeology@lakedistrict.gov.uk or 01539 724555).

Maintaining traditional practices are essential for the World Heritage Site, but they are also crucial to perpetuating our farming system and our businesses. It will also aid in farming-led nature recovery of our biodiversity, as part of the Government’s 25 year Environment Plan, through actions such as the right stocking balance.

Commoning and heft management are an integral part of many Lake District farms; whereby the behavioural instinct of sheep is applied to keep them on an unfenced piece of land.

Appreciating the complexities of heaf operation is essential for all land management stakeholders in the Lake District. Reducing stocking rates, whilst straightforward on paper, can have negative repercussions across farm businesses as numbers become so low that the practicality of every day management becomes a challenge to manage. At the same time increasing rates can damage biodiversity through overgrazing.

The skill is identifying appropriate stocking rates that are a ‘sweet spot’ between practical management and biodiversity gain. The challenge is recognising that this spot is different for every fell, with an appropriate minimum and maximum of numbers for each particular place. Helping to identify this sweet spot is an aim of the Lake District Partnership.

Often misunderstood as a corrupted form of English, Cumbrian is actually the root of many modern English words and some argue it is more than just local dialect, but a language in its own right derived from Norse and Old English. There are many commonplace words we use to describe our landscape such as ghyll, beck and fell. Syntax also has a life of its own, for instance the word ‘the’ is contracted to just ‘t’, such as in “t’wood in t’wohl” - shut the door.

Many farming practices employ dialect words and consequently form a crucial component of maintaining our cultural heritage. Counting stock in particular—Yan, Tan, Tethera …..

Image: A Lakeland agricultural show

Our Lakeland agricultural shows and shepherds meets provide an opportunity to show livestock, learn about the latest technology, meet socially with your peers and support a younger generation of farmers. They create a platform for businesses to trade and, increasingly, a way of demonstrating our green credentials.

These shows are also crucial for the general public allowing us to communicate why they should support Lake District farming and our high quality food production. They showcase how our farming assists natural and cultural heritage and they provide a shopfront for selling direct to consumers, which is important for farm businesses wanting to diversify.

Your continued support to plan, organise and visit our shows and meets is greatly appreciated by the World Heritage Site Steering Group and Lake District Partnership.

Image: Stonewalling © Rusland Horizons Trust

Without traditional skills everything in our farmed landscape cannot be maintained or enhanced. Whilst some skills such as drystone walling, gathering and sheep dog handling are central to farming in the Lake District, there are other more specialist skills that are under threat. Pollarding, slating and bee skep making are three skills that appear on the Heritage Crafts Red List of Endangered Crafts. Farm skills transmission to the next generation of Lake District farmers is essential. We all play our part here by sharing our knowledge with young people.

Our agro-pastoral farming is important in three key ways. First, research shows the actual farming techniques you employ have created over 44% of the UK’s semi-natural habitats (See Osterman, 1998). Second, any low intensity practices you use keep nutrient levels low, which encourage plant diversity supporting a greater range of insects, birds and animals. Finally, your traditional buildings provide roosts, nesting sites and food sources for birds and bats in particular.

Consequently, practices which intensify farming practice are strongly discouraged and are often the focus of agri-environment schemes. Hence silaging, applying slurry or NPK are less welcome. Finding the balance between fodder production and biodi-versity management can therefore be complex.

Nine of our 14 British bats have been recorded in Cumbria. All bat roosts are protected by law and thus if you are planning any roofing works where there are bats contacting Natural England is key. They are particularly vulnerable when they are hibernating in winter. New roosts can also be created using several boxes in outlying barns. They like cover nearby so planting native trees, honeysuckle and ivy is preferable.

Image: Owl box: © RSPB, Grahame Madge

Barns are the best place to put in an owl box. They are easy to erect, quick and cheap to make, last about ten years and afford excellent shelter for the owl. Things to consider for owl boxes:

Image: Haymeadow: © Michelle Hughes, 2016

Hay meadows are some of our richest flowering plant communities supporting insects, pollinators and bird life. Changes in farming practices have favoured silage over hay in the last 50 years; damaging biodiversity. While switching back to hay is often supported by agri-environment grants, there are also savings by not buying plastic. Climate change may also help as we get longer, drier summers for more effective hay making.

Rough grazing makes ideal habitat for owls. They are seeking patches or strips of vegeta-tion with a high field vole population.

Image: rough grazing in the Lake District

Thick, matted, tussocky mix of native grass species with a good litter layer at least 7cm (3″) deep are key. The land needs to be more than 1km away from fast open-plan roads to reduce road deaths.

These pollarded ash at Dowthwaite are the remnants of historical cropping of different sized ash for hurdles, hedging stakes, animal fodder, firewood and charcoal. They provide homes for various harmless fungi which can support up to 2000 species of invertebrates, as well as bird nests and bat roosts. Pollinators such as bees are under direct threat from industrial agriculture and the use of inappropriate pesticides.

Image: Pollarded Ash at Dowthwaite

Restoring traditional bee boles in wall cavities, such as these at Finsthwaite, provide lodgings for straw bee skeps for illustrative purposes only.

Image: traditional Bee Boles, Finsthwaite

Agriculture is being asked to help with climate change in two main ways; first, by reducing the amount of Greenhouse Gases emitted by their enterprises and second, to lock up (sequester) carbon in soil, peat and vegetation.

The best way to do this is to ensure you have a carbon audit, this provides a baseline of how much carbon you are emitting and sequestering right now. From this you can then make changes that reduce emissions and increase sequestration. The new 2022 Sustainable Farming Incentive will be useful here. Carbon audits are not just about saving carbon, they can also aid in farm productivity and the bottom line. There are several free tools available which do not need you to employ a farm adviser. Some look at separate enterprises, others look at the whole farm:

are currently the most used. Buildings can also contribute to carbon management throughout their whole lives. Traditional stone buildings are much better than new builds made from concrete and steel as the carbon is already embedded (locked in). New builds create large quantities of carbon through the manufacture of materials, transportation and construction. Retrofitting traditional buildings, whether farmhouses or barn conversions, using natural, sustainable materials and techniques, will save carbon and money on bills. An example of this is using carbon neutral insulation (wool, cork, hempcrete or cellulose) rather than rockwool, expanded polystyrene or fibreglass which emit significant carbon in their production & transport.

Low Carbon technologies related to renewable energy, low emission transport & machinery as well innovations in technology all help reduce the farm’s carbon footprint. Pico (under 5kW) and Micro (5 to 100kW) hydro power are becoming increasingly popular in upland areas. For example at Hayeswater in the Ullswater Valley, installed by the National Trust in 2017. Find out more by visiting the annual Low Carbon Agriculture Show at Stoneleigh in March or by following it online.

Most soils contain around 5% carbon as organic matter, whereas in peat, it can be as much as 100%. Carbon sequestration is a term used to describe methods to lock up even more carbon. Planting trees, managing woods, grazing rather mowing, improving soil health, restoring & maintaining peat and increasing biodiversity all help. Particularly important is improving the quality of our lowland and upland peats through effective water control and vegetation recovery.

Image: Peat photographed by © Lois Mansfield, at Mungrisedale common

Farm woods have been an integral part of the farmed landscape for generations. Recent cost of production pressures have resulted in many being undermanaged as time has been diverted elsewhere, but we need to keep our woods for our WHS Outstanding Universal Value. Diversification opportunities exist by exploiting current timber markets as well as new ones, as we seek to move away from plastics and back to wooden product.

New grants, such as ELMS and the SFI, will be on offer soon to encourage climate action and biodiversity management. In the meantime, if you have been inspired by this booklet please apply for a Farming in Protected Landscapes (FiPL) grant that allows you to combine climate action and biodiversity management with visitors needs (such as rights of way) and the cultural heritage of your farm (see cover for details).

Ring: 07766 367529 to speak to the Lake District Farming Officer

Content on this page is based on a leaflet produced under Valuing Our Cultural Landscapes project generously funded by the Lake District Farming in Protected Landscapes Programme.

Image acknowledgements: ‘An Approach to Landscape Character Assessment’ © Natural England 2014 p4; H Meanwell, p11; Cumberland Bat Group p12; NFU Carbon Audit logo p14; Rusland Horizons Trust p8 & 11, RSPB p12/13. Lake District Farmers.

@Design and text taken from a leaflet by l. Mansfield 2022. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons

Find Out More: Buildings

Find Out More: Landscapes

Find Out More: Habitats

Find Out More : Climate Action

Ring: 07766 367529 to speak to the Lake District Farming Officer